Part 1 of this blog post explored some starting points and contexts for the introduction of coaching and coaching approaches in schools. In this post I’d like to consider what we might see happening as coaching evolves in context. How might a coaching culture emerge and what does it look like?

The definition above suggests that a coaching culture is one where the organisation has moved beyond seeing coaching as an isolated intervention, perhaps targeting specific issues. Coaching is now embedded as part of the organisational way of working, as indicated by its deliberate integration into strategic planning. Further, broader collegial benefits are identified and the use of ‘coaching approaches’ has been extended to include stakeholders other than just employees.

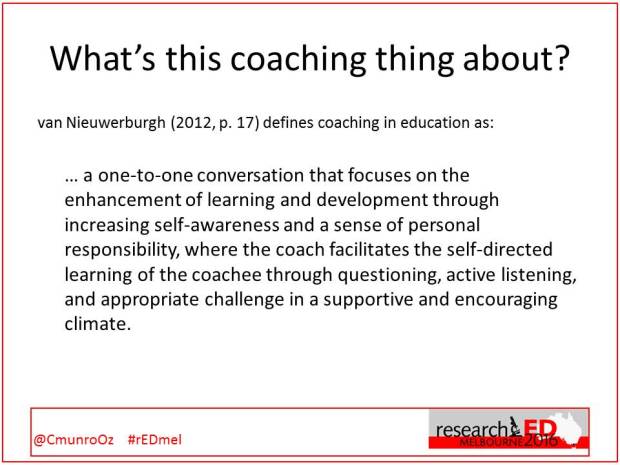

In Part 1, I outlined a range of conversational contexts or ‘portals’ through which coaching might be introduced in schools. I touched on the importance of clarity of intent, rationale, and organisational factors in the success of what probably begins life as ‘another initiative’. Once the starting point and broad rationale are identified, the way in which the initiative is led, by whom, with whom, and at what speed, is highly contextual. In this excellent book chapter, Christian van Nieuwerburgh synthesises a range of research on coaching cultures and identifies some helpful frameworks to describe the evolution of such cultures. Clutterbuck and Megginson’s (2005) four stages of development towards a coaching culture more or less describe the phases that we’ve gone through in my own school context:

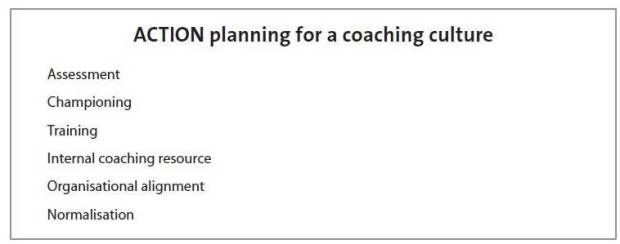

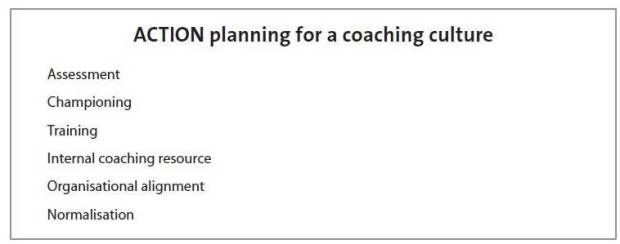

The broad stages outline by van Nieuwerburgh using the ACTION acronym also fit well with our development process – albeit not quite so linear!

I would not claim that my school has a fully embedded coaching culture and has reached the ‘normalisation’ stage – yet. However, I have witnessed what might be described as the embryonic signs of a coaching culture. More than three years since the introduction of the idea of coaching at the school, we can now see its influence across a wider range of contexts than we had first intended. The true test will be if the influence of coaching continues to grow and is sustained over the next few years. I am optimistic that it will.

We initially proposed coaching as a vehicle to enhance professional practice and to catalyze professional learning in a way that respected the professionalism of teachers. I have been very privileged to be given license to champion this approach as the main plank of our emerging professional learning strategy and lucky not to have to juggle this with competing ‘initiatives’. I know from past experience that this is not always the case in schools. You can read more about how we articulated our coaching model here.

Our coaching journey began with two ‘in-training’ coaches on our Secondary campuses offering a cycle of six or seven coaching sessions to teacher volunteers on any aspect of their practice. (We also had a Teaching & Learning Coach establishing a parallel role at our Primary campus 3 days per week).

After taking is slow, building trust in the process and personnel, and continuing to champion the approach at all levels, it is gratifying to see the fruits of our labours take shape. The evolution of our coaching approach (so far) can best be illustrated with the following examples:

Forms of Coaching

1-1 Coaching continues to be offered as a professional learning ‘service’. The uptake of this option has grown rapidly as more teachers experience it and word (and trust) spreads.

Internal ‘Executive Coaching’ was also offered to a target group of middle and senior school leaders with a view to focusing on their leadership roles and responsibilities. This was very well received and created more advocates in positions of influence.

Scaling-up access to coaching for a large Secondary school staff continues to be a significant challenge given the limited capacity of the coaches. One way of addressing this was the introduction of Peer-Coaching. Pairs of teachers were invited to be ‘trained’ in the use of a coaching approach in collegial discussions about practice. Again, there was a healthy appetite for this non-threatening reciprocal approach to classroom observation and feedback.

REALITY CHECK: There is a need for strategic investment to support this work – time! Teachers are finding time and space for this because they know what they are getting out of it. However, this cannot be maintained on good-will alone and schools need to consider what they might need to do differently, or stop doing, to support this new kind of professional learning.

Coaching Approaches to Performance & Development Conversations

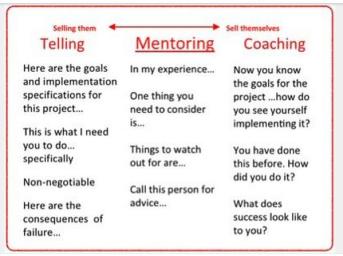

The development of coaching skills and approaches with our school leaders (many of whom had been coached) was viewed as an important investment to support our recently revised approach to Performance and Development planning. It has also proved extremely worthwhile from a general leadership development point of view.

The intent of the Performance and Development Framework is to recognise, enhance and build upon the outstanding work of our staff so that they may continue to grow as members of our professional community. The Framework is intended to provide for a collaborative, growth-orientated process – not a punitive appraisal in the traditional sense. The process does not start from a deficit point of view. It is primarily about having better conversations about our practice so that we continue to strive to be the best educators we can be for the children in our care. As members of a professional community, we have a responsibility to routinely reflect, develop, and seek feedback on our practice so that we remain fully engaged in our work as professional educators.

The Leader as Coach program (a bespoke version of this program) was delivered over four twilight sessions. The aim of the program was to provide a frame for collegial dialogue between the leaders and their teams and/or P&D groups. The dynamic and outcomes of these sessions is something that I’ll write about at a later stage. We have not magically turned our leaders into coaches but we hope that we have sown the seeds, and introduced some skills, that will be sustained and further developed going forward. This may well need more coaching!

eLearning Fixer to eLearning Coach

The experience of our Head of eLearning, Phil Feain, serves as a great example of the transformative impact of coaching. As you might expect, he is passionate about the role of technology in supporting learning. He very much sees his role as one of supporting student learning through his advocacy of appropriate eLearning tools and strategies. He is NOT the Network Manager or a tech-support person (although he does know this stuff!).

Phil approached our coaching pilot with curiosity and caution. He thought that it sounded like a different kind of learning opportunity for staff but had a healthy suspicion of the latest fads (and to be fair, my motives, as I was a new to the school too).

He took part in our introductory sessions and liked what he saw and heard. When we targeted school leaders with an invitation to be coached Phil took up the offer and we started working on a couple of goal areas around his leadership role. His main concern was that he wanted to move from spending the bulk of his time as a tech-fixer or demonstrator to having more of a focus on the learning aspect of his eLearning role. Through being coached he was able to enact new ways of engaging with staff and initiate new opportunities to generate more two-way traffic in his role. One way that he has done this is by offering eLearning Coaching as part of our Professional Learning Program this year. In this role Phil is adopting a coaching approach to supporting staff to achieve their eLearning goals. Success! – for Phil and the coaching program.

So when we offered introductory training to get Peer-Coaching off the ground, Phil was one of the first to sign-up. He partnered with a colleague in another subject area and embarked on a reciprocal series of coaching sessions over the year thus gaining more coaching experience and learning as he went.

As one of the school’s middle-leaders, Phil was also involved in the Leader as Coach program. This experience is enabling him to begin to apply his growing coaching skills and experience to his role as a subject team leader.

For me, the most significant and pleasing part of this story is that Phil has been the first to open another coaching ‘portal’ by exploring the application of his coaching skills in academic progress conversations with his Year 12 students.

Similarly, it did not take long for our pastoral leaders who were coached or took part in the Leader as Coach program to begin talking about the potential of this approach with students, and even parents. This is most likely the next natural development for us.

Coaching as Part of Strategic Plans

Positions of leadership at our school are reappointed every four years. We are in the midst of this process at the moment and this has presented the opportunity to update role descriptions and review current requirements. As a result, my own position, Dean of Professional Practice, now has coaching, and leadership of coaching, explicitly stated in the role description. Based on the success of our work to date, and the persuasive effect of this on the senior leadership of the school, our coaching team will expand and be formalised in 2017 with the creation of two new substantive positions of Secondary Learning and Teaching Coach. These strategic moves can only strengthen the place of coaching in the school learning culture going forward.

A Coaching Culture?

So what are the signs that a coaching culture might be emerging? This slide suggests some (coaching) questions that we might ask ourselves and points to some possible answers. What could this look like in your school context?

References

Clutterbuck, D., & Megginson, D. (2005) Making Coaching Work: Creating a Coaching Culture. London: CIPD.

Gormley, H., & van Nieuwerburgh, C. (2014). Developing coaching cultures: a review of the literature. Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 7: 90-101.

van Nieuwerburgh, C. (2016). Towards a coaching culture. In C. van Nieuwerburgh (Ed.) Coaching in Professional Contexts. (pp.227-234). London: Sage.